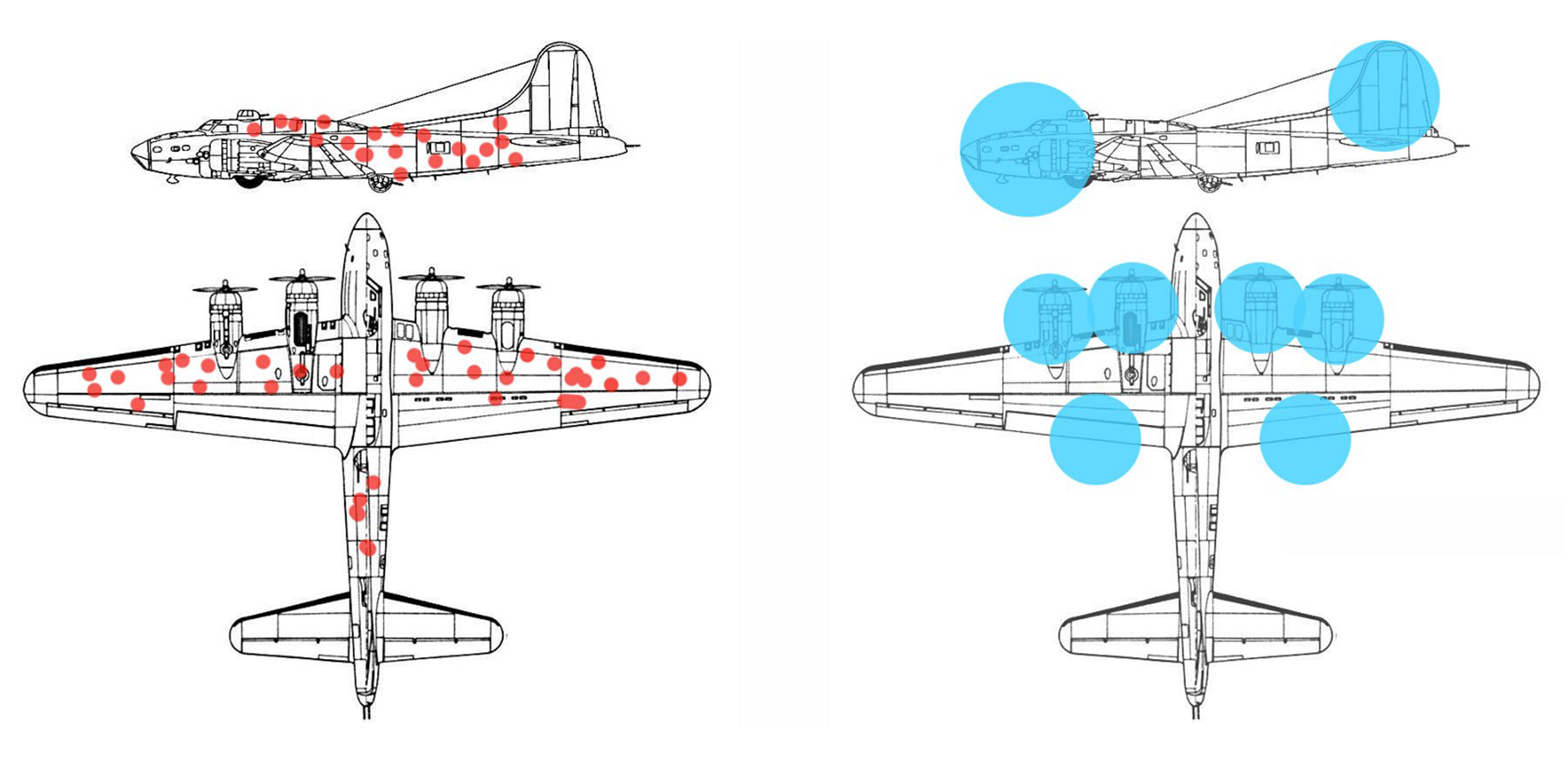

There is a story that I am very fond of—a story that seems, to be honest, a bit too beautiful to be true. However, it has basically been proven scientifically. This story is that of Abraham Wald and his statistics colleagues at Columbia University during World War II. With the goal of cutting down on the loss of human lives and ensuring that the US had the upper hand in aerial combat, some people endeavored to reinforce the parts of the fighter planes that were hit most often by enemy fire.

This seems perfectly logical at first glance. Except that Abraham Wald proposed a different working hypothesis. His hypothesis was based on the principle that all of the studies that had been completed were of planes that had returned home safely, even if they had been hit. So, what had happened to the planes that had, sadly, gone down and of which there was no trace? Weren’t the parts of the planes that they thought were the weakest actually the strongest? Instead, didn’t they need to consider reinforcing the parts of the planes that were not hit since those were, in fact, the most susceptible to causing planes to go down if they were hit?

Survivorship Bias

Abraham Wald’s hypothesis took into account ‘survivorship bias’. To give a very short definition, survivorship bias is the idea that we often have a tendency to concentrate on the statistical exceptions. However, those exceptions don’t necessarily represent the whole picture. For example, as a head of school, people often like to tell me about a few very rich and well-known CEOs who left school early as a way of trying to get me to believe that education doesn’t really matter.

After a few weeks at The École, this logical bias seems to me to be more and more useful and efficient as an analytical tool that will allow us to shake things up in order to progress. For didn’t I have in front of me a close-knit and happy community that was so proud of its school? Didn’t I have a qualified, experienced and very talented team of teachers? Didn’t we offer a sophisticated and well-thought-out bilingual program that is more accomplished than those that I have come across elsewhere? Under these conditions, what can we change, or rather, what do we want to change?

A New Hypothesis for The École

So, I put forward a different hypothesis, which was completely made up and a bit thought-provoking but that allowed me to mull things over and go further in my reflection. This hypothesis was that we, all of us, in what we do and in our passion for The École, are a statistical exception. There is another, much larger community that really did not want to come to The École. That community didn’t even know The École, or worse yet, it didn’t even like it. This other community was not satisfied with the teachers or the curriculum, and they left for another school.

In trying to convince that other community, I came up with some new ideas. Those ideas are going to be put into place starting in September. I will tell you more about them in the coming weeks. It goes without saying: we can, and must, always be improving and strengthening our program. Like those parts of the plane that are already solid, what we do and what we offer is high quality and it works well. When we look at what we are not doing yet, when we focus also on what we are not as a school but what we want to become, then we can start to dream about serving an ever larger and more diverse community, and always for longer.

In making you love The École even more, we will make it even more loved by others in the future.